home gnus boomer boneyard links trackplan recent layout pix

| BACKGROUND | NEW ORIENTAL | OPERATION | MARKETING | LEGACY | BIBLIGROPHY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOTIVE POWER | HEADEND | COACHES | DINER | SLEEPERS | OBSERVATION |

Part 1 GNRHS Reference Sheet #273 dated June 1999 Part 2 GNRHS Reference Sheet #280 dated March 2000

This background reference sheet introduces the early trains operated by the Great Northern. It is focused on building the line, and developing passenger service as they evolved between 1886 and 1929. Early Great Northern transcontinental passenger service is a story which parallels the growth of the Northwest.

Background

Hill's Philosophy

The Great Northern Railway was James J Hill's great adventure. Of all the lines reaching the Pacific, his was unique in receiving no federal subsidy or land grant and in never falling into receivership. Hill's railroad was built without bribery, graft or chicanery. To build his line, Hill took his St. P. M. &M. where the traffic was – first up into the Red River and Manitoba wheat fields, then to the Dakota rangelands, later to Montana's copper mines, to the timber forests of the Pacific slope and finally to the Pacific ports. Hill stressed attracting settlers and emphasized economical passenger transportation. To Hill and the Great Northern, colonization was the key to expansion. Hill built the railway first, then put his energy into creating traffic for his trains. The "pay as you go" philosophy shows through at every step. He built, paused to let traffic grow, then reinvested the profits in new lines. The success of this plan for rapid expansion depended upon quick and sound colonization. Having sold the country, it was up to the railway to "make good" after the settlers moved in. Called The Empire Builder for his part in the development of the Northwest, he was one of the first to preach conservation of resources. He showed farmers improved methods of agriculture, advocated agricultural diversification, and set rates low enough so farmers could compete at distant markets. Among those he had helped to settle the land, he distributed purebred bulls, free of charge, while sending trains with exhibits and lecturers to show how agriculture could be improved. This formula enabled Hill to expand GN mileage rapidly without land grants or government subsidies of any kind, other than the limited original grant of the Minnesota & Pacific. His line became enormously profitable immediately. By the 1890s, Hill had made Minneapolis into the greatest grain milling city in America; his railroad brought in the grain, and connecting railroads shipped it out as flour.

In addition to populating the Northwest, what really mattered was that GN had the best route between the Twin Cities and Puget Sound. After completing the road to Puget Sound, GN embarked on a program to upgrade its mainline.

"A Passenger Train" Jim Hill once remarked "is like the male teat - neither useful nor ornamental." Railway Age said "Jas. J. Hill did not look favorable on passenger business". These and similar comments fostered a false perception that Hill was interested in handling freight while allowing most of the passenger traffic to gravitate to the NP. The NP offered more scenery, while the GN had lower grades which could more efficiently transport freight. However, the statement does not square with facts: GN set low rates, acquired the best quality passenger equipment, and developed steamship operations intended for passenger traffic. The GN was built through uninhabited territory which did not initially support extensive passenger traffic. Hill's idea was to build slowly and well - not laying any track which would not pay for itself. With lower operating costs and faster passenger schedules Great Northern prospered and avoided bankruptcy. By 1901, Great Northern's success enabled it to purchase the NP and CBQ.

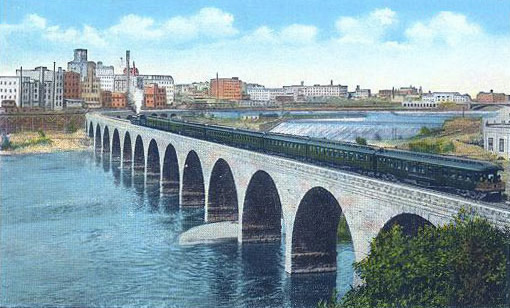

Mount Index in the Cascades,exemplifies the terrainIn 1879 Jas. J. Hill began building the Manitoba Road into a transcontinental railway. The Manitoba was pushed westward along the banks of ten great rivers, across the great plains of Minnesota and North Dakota, through the Montana and Idaho Rockies,and then over the Washington's Cascade mountains to Puget Sound and Seattle. The Great Northern's crossing of the west left a legend of a pass, which provided the lowest elevation and the shortest route. It was typical of the canny Hill that the drama was in the finding of an easy route, rather than in the conquest of a difficult one.

Starting in 1886, the St Paul, Minnesota

& Manitoba Road offered connecting service to Puget Sound over the rails

of the Canadian Pacific. The service between St. Paul and Vancouver, known

as the Manitoba- Pacific Route, continued until July, 1893. In 1888, a second

route to the west coast, called the Montana-Pacific Route, was opened via

Butte and the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company. The St. P M &M

portion of the route, known as the Montana Express, to Great Falls and Butte

flourished.

When Hill decided in 1889 that the time had come to go to the Puget Sound, he was determined to go by the shortest, most direct line. As he said " If the best and shortest means braving a more northerly clime than the N.P. - well and good."

By 1892, more direct service to Portland via the OR&N connection

at Spokane was in operation.

First Railroads in Northwest

Oregon Railway & Navigation Company

The Oregon Railway & Navigation Company was the first railway of

transcontinental consequence to operate in the Northwest. Built initially

as a short rail by-pass to circumvent the impassable rapids in the Columbia

Gorge, the OR&N grew in time and would carry the first trains to

the West Coast for the Northern Pacific, Union Pacific and the Great Northern. The OR&N used the Columbia Gorge

cross the Cascade range at water level and it continued to follow the

Columbia to eastern Oregon and Washington. In September, 1883, the OR&N

met the NP at Wallula, W.T. Portland, the largest city in the Northwest,

became a transcontinental terminus, a claim that neither Northwest rivals,

Tacoma nor Seattle, could make. OR&N's passenger trains were known

as the Atlantic & Pacific Express, Numbers 1&2. In November

of the next year, the OR&N reached Huntington, Oregon, a month after

the UP's Oregon Short Line arrived from the East. The first OSL through-train

to Portland ran on December 1, 1884. It was OSL's Number 5, connecting

with OR&N #1, the Pacific Express. Eastbound, OR&N #2, the Atlantic

Express left Portland to connect with OSL #6 at Huntington. OR&N

then had two transcontinental connections: with NP at Wallula to St.

Paul and the OSL at Huntington to the UP and Chicago .

By 1888, OR&N was operating two passenger trains

each way to and from Portland. No 1&2 took the long route to Dayton

via Wallula where it meet the NP. No 3&4, crossed the Blue Mountains

to meet the OSL at Huntington and continued on to Pocatello and Ogden.

In 1889, the OR&N built to Spokane, inaugurating passenger service

October, 1889. The OR&N depot, completed in 1890, was jointly managed

by the OR&N and the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway Company.

The schedule allowed the traveler to depart Portland at 9:30 PM to reach

Spokane at 8:40 the next evening. In the opposite direction, the train

left Spokane at 7:30 PM and passengers arrived in Portland at 6:40 PM.

The OR&N would play a role in GN's transcontinental service twice:

first as part of the Montana-Pacific Route via Butte, and second as

GN's Portland connection after its 1892 arrival in Spokane.

By 1888, OR&N was operating two passenger trains

each way to and from Portland. No 1&2 took the long route to Dayton

via Wallula where it meet the NP. No 3&4, crossed the Blue Mountains

to meet the OSL at Huntington and continued on to Pocatello and Ogden.

In 1889, the OR&N built to Spokane, inaugurating passenger service

October, 1889. The OR&N depot, completed in 1890, was jointly managed

by the OR&N and the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway Company.

The schedule allowed the traveler to depart Portland at 9:30 PM to reach

Spokane at 8:40 the next evening. In the opposite direction, the train

left Spokane at 7:30 PM and passengers arrived in Portland at 6:40 PM.

The OR&N would play a role in GN's transcontinental service twice:

first as part of the Montana-Pacific Route via Butte, and second as

GN's Portland connection after its 1892 arrival in Spokane.

Northern Pacific

"The Northern Pacific, completed ten years before the Great Northern,

was the first transcontinental across the Northwest", according

to Martin Albo. "The Northern Pacific, built with subsidies and

land grants, had used its ten year head start to buildup traffic, establish

operations and acquire equipment. However, it was poorly routed, poorly

engineered and poorly managed. Hill realized the potential for a competently

engineered and efficiently operated railroad that could successfully

compete with the Northern Pacific".

Like the Union Pacific and Great Northern, the Northern Pacific's first western terminal was Portland, Oregon, reached over the rails of the OR&N on the south bank of the Columbia. In 1873, NP built a line from Kalama, 40 miles north of Portland, to Tacoma. On September 12, 1883, Transcontinental service was inaugurated from St Paul to Tacoma via Portland. The Northern Pacific's direct line from Spokane Falls and Pasco reached its western terminal of Tacoma in July, 1887, via a series of switchbacks over the crest of the Cascades while its 1.8 mile tunnel was being bored. On June 2, 1888, NP witnessed its first train through Stampede Tunnel. The crossing was very similar to GN's Steven's Pass line a decade later. An 1887 advertisement bolstered that it "was the only transcontinental line running diners of any description." In the east, the Wisconsin Central was leased by the N.P.to provide for direct service to Chicago.

On June 15, 1890, N.P. began operating two first class trains, spaced

one half day apart, on a 76 hour schedule. Trains 1 & 2, the Atlantic

and Pacific Mail, ran from Seattle/Tacoma to Chicago via Helena and

St. Paul. Trains 3 & 4, the Atlantic and Pacific Express, ran from

Tacoma to Chicago via Butte and St. Paul. Westbound, No

1 departed St. Paul at 4:15 PM and No. 3's departure was set for 9:00

AM . Eastbound, No 4 departed Tacoma at 12:40 noon and No 2 left at

6:05 PM. Both trains carried first class and tourist sleepers, first

and second class coaches, colonist cars and a diner. By the time of

Great Northern's arrival in 1893, NP's passenger service had been established

for several years and it carried finer equipment. It no longer used

the OR&N as an Oregon connection, instead routing its traffic to

Portland via Tacoma on its own west coast line with a 101 hour schedule

from St Paul.

The North Coast Limited, inaugurated as a summer only train, on April 29, 1900, set a new standard for luxury travel to the Pacific Northwest. It was the first electrically lit passenger train to Puget Sound. Its steam heated cars featured wide vestibules which were richly finished inside in mahogany and leather. Each train had smoking and card rooms and introduced a barbershop and valet, bathtubs with showers and other frills. The NCL's success resulted in year round operations by May, 1901. Its schedule for the 2056 miles from St. Paul to Seattle was 62 hours. Although a better train than the GN Flyer, it required an additional 2-1/2 hours to reach St Paul.

Canadian Pacific

In 1880, Stephen invited Hill to join the CPR syndicate. By 1881, Hill had joined the CPR executive committee. He selected the direct route west through Kicking Horse Pass; brought in talented individuals including Van Horne as manager; made personal loans when CPR was short of cash; and sent aid and emergency supplies during a crisis. Hill viewed the CPR as St.P.M.&M's direct extension to the coast, with the Manitoba Road furnishing the North-South link. Instead of building around the north shore of Lake Superior, Hill felt the eastern link should be routed over the rails of the St.P.M.&M through the U.S., re-entering Canada at Sault St. Marie, Ontario. When the Canadian Government mandated an all-Canadian route, he resigned.

Canadian Pacific was the second transcontinental

to reach the Pacific Northwest in November, 1885. The Canadian Pacific

Railway began transcontinental passenger service in June, 1886. Its

route crossed the vast Canadian prairies west from Winnipeg, entering

the Rocky mountains east of Banff. The CPR route traversed the Rockies by a torturous 4% grade over Kicking Horse Pass, then on to

the Selkirk Range where more extreme grades were encountered at Rogers

Pass before finally reaching the Fraser River. The railway utilized

the narrow Fraser Canyon to pass through the Coast Range to tidewater.

The crossing of the the Rockies and Selkirks was so difficult through

this portion of the line that it chose not to haul diners on its passenger

trains. Meal stops were made at three division points. These were locations

selected for their magnificent settings: Field, west of Kicking Horse

Pass, Glacier at the base of Rogers Pass and North Bend, before entering

the Fraser Canyon. While locomotives were being changed and the train

serviced, westbound passengers ate breakfast at Field's Mount Stephen

House, lunch at Glacier House, and supper at North Bend's Fraser Canyon

House. Eastbound, the meal stops were reversed. These meal stops operated

until 1909 when diners were added to the trains.

Canadian Pacific obtained the finest equipment available for its trains from Barney & Smith. Railroad promotional material provided glowing descriptions as in this Canadian Pacific advertisement found in Arthur Dubin's Some Classic Trains. Sleeping cars are fitted up with oiled walnut, carved and gilded, etched and stained plate glass, metal trappings heavy silver plated, seats cushioned with thick plushes, wash stands of marble and walnut, damask curtains and massive mirrors in frames of gilded walnut. Floors are carpeted with the most costly Brussels material and the roof beautifully frescoed in mosaics of gold, emerald, green, crimson, sky blue, violet, drab and black"

The CPR transcontinental trains, referred to as the Atlantic and Pacific Express, carried no numbers. The six day transcontinental journey from Montreal to Vancouver operated six days a week.

Pre-1893 Great Northern Service

Jas. J. Hill played a significant role in the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway west of the Great Lakes. Canadians George Stephen and Donald Smith, who had helped Hill secure the St. P. M&M in 1879 and continued to be principle stockholders of the St. P.M.&M, were part of the initial CPR syndicate. The Manitoba's first transcontinental link was via the CPR.

The St. P. & P.'s switcher 192 at work in St. Paul. Note the road's yellow coach in the background. |

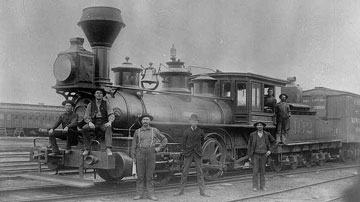

Beginning in the late 1870's, the St.P.M.&M offered service from St. Paul to Winnipeg via two routes. Trains 9&10 followed the line on the east side of the Red River through St Vincent, MN, connecting with the CPR at Emerson, Manitoba. Trains 3&4 followed the line on the west side of the Red River through Neche, ND, connecting with the CPR at Gretna, Manitoba. The Manitoba Road's equipment was typical for 1880's passenger service: American standard 4-4-0's pulling 50' open platform coaches sleepers, and baggage cars, riding on four wheel trucks.

St. P & P and St. M &M passenger cars were yellow until

about 1883. Beginning in 1883 the St. M & M cars began to be painted

maroon. As fully described in Ref Sheet 238, the Manitoba Road, in 1883,received

eight 12 section sleepers which also had state and smoking rooms. Judging

from the car names of Anoka, Northcote, Minnewaka, Mille Lacs, Wamduska,

St. Hilaire, Wahpeton, and Wayzata, the cars were used in Winnipeg service.

The St. P. & P.'s first roundhouse about the time Hill and associates took over the pike. The St. P. & P.'s first roundhouse about the time Hill and associates took over the pike. |

By 1885, the Winnipeg trains originated and terminated at St Paul's new Union Depot. Trains 3 & 4 ran alternately via Elk River or Osseo to St Cloud. From there they ran north to Fergus Falls, Barnesville, then across the Red River to Fargo, N.D., Grand Forks, Grafton and Neche, N.D., to Gretna, Manitoba. Trains 9 & 10 operated via Willmar, Morris, Breckenridge, Wahpeton, Barnesville, Crookston, St Vincent, Minnesota to Emerson, Manitoba. CPR's connections to Winnipeg were made at both Gretna and Emerson.

From Winnipeg, CPR provided service east to Rat Portage, present day Kenora Ont. and west to Swift Current, Sask. Sleeping car service to Winnipeg was offered on trains 9&10. Train #9 departed St. Paul at 9:30 PM arriving in Winnipeg at 5:25 PM the next day. Train #10 departed Winnipeg at 6:45 AM, reaching St. Paul at 7:30 am on the next day. Through sleepers were carried on trains 3&4 only between St Paul and Grand Forks.

Manitoba-Pacific Route

Hill realized early that without a Pacific connection, the Manitoba

would sooner or later wither away. In 1883, it was obvious that the

CPR would not serve as the Manitoba's Pacific connection and decided

to build his own line to Puget Sound. Hill wanted the St.P.M.&M

to participate in the traffic to the coast immediately, while its own line was being built. He made arrangements through Stephen,

Director of the CPR, to carry passengers and freight over St.P.M. &M

from St. Paul to Winnipeg and then over the CPR to the Pacific coast

in what became known as the Manitoba-Pacific

Route between St. Paul - Winnipeg - Vancouver. It was understood

that this arrangement would terminate when Hill's own line to the coast

was completed.

Initially in 1886, the Manitoba- Pacific through cars were operated north on train #10 and returned south on train #3. Numbers 3 & 10 carried a baggage car, coaches and sleepers to Winnipeg. The timetables indicate colonist cars and first class sleepers were assigned to through service' to the coast. On Tuesdays and Fridays, St. P. M & M sleepers were transferred to the CPR for the remainder of the trip to the West Coast. The service soon became tri-weekly and by 1889, service was offered daily. By 1891, trains 9 & 10 carried the Manitoba-Pacific both ways over the line through Gretna, Grand Forks, Fargo, Breckenridge,and Willmar. The Manitoba- Pacific continued to be operated over the Gretna route until the end of service in 1893

.

| FROM | OFFICIAL GUIDE | 1886 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WESTBOUND #3 | St.P M & M Ry | EASTBOUND #10 | ||

| (Sunday) | Dep 6:40 PM | St Paul | Ar 7:15 AM | (Saturday) |

| (Monday) | Arr 1:50 PM | Winnipeg | Lv 10:45 AM | (Friday) |

| The Pacific Express | Canadian Pacific Ry | The Atlantic Express | ||

| (Monday) | Dep 4:25 PM | Winnipeg | Arr 4:30 PM | (Thursday) |

| (Thursday) | Arr 5:10 PM | Vancouver | Lv 1:00 PM | (Monday) |

From Winnipeg, it was a 76-1/2 hour trip

to the Coast. In 1888, the Manitoba Road acquired 14 additional sleepers

from Barney & Smith (See Ref sheet 238). Eight were Colonist Sleepers,

no 450-457. The six first class sleepers, No 225-30, were the first

vestibuled sleepers on the railroad and were named Buford, St Vincent,

Benton, Boulder, Neche, and Assiniboine. The timetables state that colonist

cars and standard sleepers went "through to the coast", two

days a week. It is probable that the eight colonist cars were acquired

for the Manitoba-Pacific service. Three of the six sleepers were named

for stations on the Winnipeg line and probably supplemented the eight

acquired in 1883. The other three were probably assigned to the new

Montana line. Fort Buford was the original name of Williston, ND; Fort

Assissiborne was close to Havre MT; Fort Benton is northwest of Great

Falls, Montana.

At the original CPR terminus of Port Moody, the steamer Yosemite, under contract to the CPR, formed the final link of the route. It met the train and carried freight and passengers to Victoria and Seattle. On May 23, 1887, the CPR moved its western terminal to Vancouver, and the Manitoba-Pacific connection with the Yosemite was moved to New Westminister. On Puget Sound, the vessels of the famous mosquito fleet served other ports from Seattle. This service remained in operation until June 1893, when Great Northern began its own passenger trains to Seattle.

Later Manitoba - Pacific travel times

| Spring 1891 | ||

| Westbound | ||

| (Mon) | Depart : 6:30 PM | St. Paul |

| (Fri) | Arrive : 9:10 PM | Seattle |

| Running Time 100:30 hours | ||

| Milage 2127 (by boat) |

| March 1893 | ||

| Westbound | ||

| (Mon) | Depart : 6:33 PM | St. Paul |

| (Fri) | Arrive : 5:40 PM | Seattle |

| Running Time 97 hours | ||

| Milage 2053 (by rail) |

Great Northern's Coast line

Beginning with his withdrawal from the CPR Board of Directors in 1883,

Hill had his eye on his own line to the Pacific coast. As traffic and

revenues built in the east, he began cultivating sources of traffic

on Puget Sound. His efforts became apparent in the late 1880's. Using

the famous Head of Rake analogy, Hill concluded tha traffic could be

generated from all the Puget Sound ports and funneled through one line

East. GN only needed to build a line along the entire Sound. Before

its own line through the Rocky Mountains was started, Great Northern

was organizing its 'head of the rake', a line along both the

North and South ends of Puget Sound. In 1889, UP surveyed a route from

Portland to Seattle and Vancouver, B.C. In anticipation of construction,

the Portland & Puget Sound (P&PS) was formed by the OR&N

and it started acquiring rights of way between Seattle and Portland.

Great Northern bought half interest in October 1890. The P&PS had

rights to build between Tacoma to Seattle via the coast, not the Green

River valley. Because of poor construction and cost overruns, the project

did not succeed and was abandoned in December, 1890. By this time, Great

Northern's intention of building to Puget Sound was widely known. Hill was courted by several Puget Sound ports

including Anacortes, New Whatcom, Everett, Olympia, Vancouver, Tacoma

and Seattle for GN's Puget Sound terminal. Hill used this to his advantage

to demand rights of way at Seattle, Everett and New Whatcom, as Bellingham

was called. Serious consideration had been given to a proposal to build

the line due west through Sherman Pass to Lake Chelan and the Cascades.

It would have descended via the more northerly Skagit Valley to reach

the coast at Bellingham Bay. New Whatcom, would have become his Pacific

Terminal. Instead, he decided, in 1890, to make Seattle, which had grown

to become the largest city in the Northwest, GN's western terminus.

The decision was reached after Seattle leaders delivered 60 acres north

of Smith's Cove for the interbay terminal and obtained a right of way

for the GN through Seattle to a place south of the city near the P&PS right

of way. The Seattle right of way also included Hill's receiving sixty

feet of Railroad Avenue's 120 foot width for use as access to the Seattle,

Lake Shore and Eastern's depot already located at the corner of Railroad

Ave and Columbia Street. The depot, also used by the NP, would continue

to be GN's western terminus for fifteen years until King Street Station

and the Seattle tunnel were completed in 1906 .

To the north, GN obtained the Fairhaven and Southern in 1889, which

had a charter to build to the Canadian border and also obtained a franchise

for the New Westminister & Southern, a Canadian pike, to provide

an entrance to Canada. On Valentine's Day, 1891, the last pike was driven

east the border town of Blaine,

completing the line between Burlington, Washington on the Skagit River

and Brownsville, B.C. acrossthe Fraser river from New Westminister with its CPR connection. That year, the Seattle

and Montana Railway built 78 miles of track from Burlington along Puget

Sound south to Seattle. The first train ran from Seattle to Brownsville

in November, 1891. The trains were numbered 1 & 2.

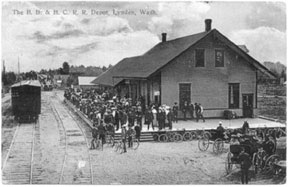

The Bellingham Bay and British Columbia depot at Lynden, Wash. |

In May 1891, CPR built a bridge over the Fraser at Mission, B.C. There, thirty-four miles up river from New Westminister, it built a line to Huntington B.C. The Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railway was being constructed at the sametime between Sehome Jct (Bellingham, WA) and Huntington B.C. via Sumas, WA. open-windowed coaches.

Shortly thereafter, the GN began advertising direct rail service, in the Official Guide, between St Paul and Seattle via the Manitoba-Pacific route: GN between St Paul and Winnipeg, the CPR between Winnipeg and New Whatcom (Sehome, Jct), and the GN again to Seattle. It is not known if the through sleepers stopped at Mission or continued to Seattle. North of New Whatcom, GN crossed the border at Blaine and Douglass, B.C. (White Rock) stopping at Brownstown, across the Fraser from NewWestminister. After a ferry ride to New Westminister, connections were offered over the rails of The Electric Company for the 14 mile trip to Vancouver. Great Northern did not enter Vancouver until 1902, when the Provincial Government built a rail-highway bridge.

| Westbound | Eastbound | |

| Northern Pacific | 45.18% | 39.46% |

| Canadian Pacific* | 33.25% | 28.95% |

| Union Pacific | 18.46% | 18.83% |

| Southern Pacific | 2.43% | 12.76% |

Source: 1890 Northern Pacific Annual report LINES WEST *Includes Manitoba-Pacific Traffic |

||

In 1891, two years before its own mainline from the east was ready, GN had built a temporary handle for its rakehead. GN trains provided service from Seattle to New Whatcom and connections with the CPR mainline. Residents along Puget Sound had easy access to the vast area served by CPR, as well as St Paul via Winnipeg. The CPR continued to carry GN passenger and freight traffic east, until July, 1893.

The old Lake Shore and Eastern depot in Seattle. The old Lake Shore and Eastern depot in Seattle. |

The Manitoba-Pacific Route was successful in drawing traffic destined for the Northwest as this chart indicates.

Dining Car Service Starts

Initially, sleeping car companies tried installing stoves

for cooking in each of their sleeping cars. In 1868, Pullman built its

first diner, the Delmonico, which found rapid acceptance on Eastern

railroads. Members of the Western Traffic Association, including the

UP, ATSF, CB&Q and St.P.M.&M, concluded that diners were unprofitable and had an agreement among themselves not to operate diners

west of the Missouri River. As the other western roads watched, change

came in 1883, when NP inaugurated dining car service. At first, this

did not cause a problem, but by 1886 there was a flow of passengers

from the UP, and CB&Q to the NP. In 1887, the passenger car vestibule was invented, which permitted passengers

to safely pass between moving cars and made the dining car possible.

The Pennsylvania Railroad added vestibule-equipped passenger cars in

1887 with other Eastern roads quickly following.

Advertising "Great Northern dining cars are permanently attached to all transcontinental trains and do away absolutely with all the rush and hurry that too often destroys a meal on the other lines. Abundance of time, the smoothest of running and the exquisite service have made the GN diner famous with ".

By 1888 competition

with the NP for traffic to the Northwest forced St.P.M.&M to inaugurate dining car service. That year, six company-owned

dining cars were put into service on the Montana line. In 1892, an additional

six dining cars were acquired for the new Pacific Extension.

In the 1890's Great Northern developed its own china patterns called Montana, Manitoba and Hill. The oldest was Montana. It was a simple Great Northern Railway in black block letters on the white plate collar.

Manitoba predated the Hill pattern and consisted

of an intertwined G and N letters.The letters were orange outlined

with brown. The Hill pattern was more elaborate, intertwining the letters

&R but continued to use the same colors.

Manitoba predated the Hill pattern and consisted

of an intertwined G and N letters.The letters were orange outlined

with brown. The Hill pattern was more elaborate, intertwining the letters

&R but continued to use the same colors.

Building West

St. P M & M and Great Northern's pre-1893 timetables refer to three lines in the west, That evolved as the railway march west. First was the Montana Line, Then the Oregon Line and finally The Washington Line.

Montana Line

As noted above, Hill had hoped to make the St. Paul,

Minneapolis and Manitoba part of the CPRs transcontinental route between

Winnipeg and Lower Ontario. When the Canadians opted for an all-Canada

route around the north shore of Lake Superior, Hill resigned from the

CPR board of Directors and decided to build his own line to the west

coast. Once Hill decided to drive the St. P. M.& M west, he made

extraordinary progress through northwest Minnesota and into the Dakota

Territory. The expansion continued at a steady pace and by the close

of 1885, its main and branch lines had grown to 1,420 miles. In 1886,

the mainline of the St Paul Minneapolis and Manitoba was expanded westward

from Devils Lake to Minot in the Dakota Territory, a place which Charles

Minot, a St P M&M Vice-President, had selflessly named for himself.

The St. P. & P.'s tracklaying crew west of Minot in 1887.

In 1887, an enormous workforce of 10,000 laborers, including 3,300 teams of horses, graded, bridged, and laid track over 640 miles of largely unsettled North Dakota and Montana prairie. Between April and mid-October, 545 miles of St.P.M.&M right of way, stretching from Minot to Great Falls was finished. By November 19, 1887, the Montana Central, a St.P.M.&M. subsidiary, completed 96 miles between Great Falls and Helena, where connections were made with the Northern Pacific.

Montana Service

| 1887 Timetable | ||||

| West bound | St. Paul Minnesota & Manitoba Ry | Eastbound | ||

| Train #3 | Train #4 | |||

| (Sun) | Lv 8:40 PM | St Paul | Ar: 6:55 AM | (Wed) |

| (Wed) | Ar 9:25 AM* | Great Falls | Ar: 4:35 PM # | (Sun) |

| Montana Central Ry | ||||

| (Wed) | Ar 4:00 PM* | Helena | Lv: 10:00 AM # | (Sun) |

| *Ex Tues | #Ex Friday |

Early in 1888, the Montana Central reached

Butte, the mining center of Montana. Upon arrival at Butte, the westward

expansion paused for two and one half years while the territory was

settled, traffic developed and equipment acquired. Unlike other western

roads, the Manitoba had to depend on increased revenues before it could

expand.

At Butte, connections were made with the U.P, which had recently built a line up from Ogden UT via Pocatello. Pocatello was the largest rail center west of the Mississippi at that time. Transcontinental service was handled by St.P.M. & M trains 3 & 4 which now ran via Elk River to St Cloud. From there they ran north to Fergus Falls, Barnesville, to Crookston. At Crookston, cars were cut out and also ran as number 3&4 to St. Vincent, MN and Emerson, Manitoba. The remainder of thetrain ran across the Red River to Grand Forks, Devil's Lake, Minot, Havre and Great Falls. At Great Falls, the connecting Montana Central trains carried no numbers. Service was daily to Havre and offered six days a week between St Paul and Helena. It should be noted that between 1885 and 1888 trains 3&4 and trains 9&10 hadswitched routes between St. Paul and Grand Forks.

In the beginning 1887 passenger trains consisted of a 4-4-0 pulling a baggage car and two or three open platform coaches, one of which had a buffet section. The cars were painted the standard ST.P.M.&.M passenger maroon. Sleepers were offered to Great Falls two days a week only, departing St Paul on Mondays and Thursdays and returning from Great Falls on Sundays and Thursdays. Dining cars were not carried at this time. Instead, sleepers were equipped with buffets, consisting of a sink and table, that was available for passengers to prepare their own meals. Advertisements sidestepped it by proclaiming "Buffet-lounge Sleeper on every train".

From 1887 the Timetable |

Montana Express | |||

| West bound | Eastbound | |||

| Train #3 | Train #4 | |||

| (Sun) | Lv 7:40 PM | St Paul | Arr: 6:55 AM | (Wed) |

| (Wed) | Arr 6:30 PM | Butte | Lv: 7:45 AM | (Sun) |

In 1887 and 1888, the St P M&P took delivery of additional passenger equipment from Barney & Smith. First came six 13 section, buffet, stateroom open platform sleepers, numbered 219-224, which bore the Montana place names of Butte, Dakota, Montana, Helena, Dearborn and Great Falls. (See reference sheet #238) Sleepers were offered on a daily basis between St Paul and Butte in late 1887. Also three 50' baggage cars were received for the Montana service. They were numbered 204-206, rode on four wheel trucks and had a single side door.

In 1888, the Manitoba also took delivery of eleven open platform coaches, numbered 83-93, which were 56' longand rode on four wheel trucks. Finally, in 1888, the St P M&M took delivery of what is believed to be its first dining cars from Barney and Smith. There were six cars in this 1888 series, originally numbered 500-505 and renumbered in the 700 series in 1892-93, when an additional five or six cars were ordered from Barney and Smith. The diners in both orders were 72' long, riding on six wheel trucks and seating 36 patrons.

The Montana - Pacific Route

By the middle of 1888, the Manitoba Road's connection

with the U.P. at Butte was carrying passengers to the Pacific coast.

By late that year, the Montana Express offered daily dining cars and

sleepers. Hill could proudly proclaim "our trains are arriving

at Butte from 4-10 hours ahead of N.P. every day."

In 1890, the St.P.M. &M advertised solid trains with dining cars on No 3&4. The Manitoba Road offered passengers service to the Portland, Ore. via Butte and the U.P. known as the Montana - Pacific Route. The St.P.M.&M portion of the 2236 mile Montana-Pacific route to Portland ran as far as Butte.

| August 1888 Montana-Pacific | ||||

| Westbound | Eastbound | |||

| ST Paul Minnesota & Manitoba | ||||

| Train #3 | Train #4 | |||

| (Sun) | Lv 7:10 PM | St Paul | Ar: 6:55 AM | (Fri ) |

| (Wed) | Ar 6:00 AM | Great Falls | Lv: 7:30 PM | (Tue) |

| Montana Central | ||||

| (Wed) | Ar 6:00 AM | Great Falls | Lv: 7:30 PM | (Tue) |

| (Wed) | Ar 6:00 AM | Butte | Lv: 7:30 PM | (Tue) |

| OR&N | ||||

| (Wed) | Lv 7:00 AM | Spokane | Ar: 7:15 PM | (Tue) |

| (Wed) | Ar 6:50 PM | Pendelton | Lv 5:42 AM | (Tue) |

| (Thu) | Ar 7:25 AM | Portland | Lv: 7:30 PM | (Mon) |

The route ran south from Butte to Pocatello on

Oregon Short Line No 5 where it joined the mainline from Ogden. Passengers

changed trains here taking OSL No 1 west. They crossed the Blue Mountains

to meet the OR&N at Huntington, Oregon and continued on to Portland.

The trip from St. Paul to Portland took almost 96 hours. The trains

featured 4-4-0s, with antlers above the headlight, pulling open platform

head-end, coach and sleeping cars. No though equipment was operated

and passengers had to change at Butte and Pocatello.

Oregon Line

Two and one half years after the Montana Line had

been completed, traffic had grown to the point that the western expansion

could continue. February 1, 1890, the St Paul, Minneapolis, & Manitoba

was leased to the Great Northern. On October 20, 1890, the Great Northern

began the 815 mile Pacific extension from west of Havre, Montana, to Puget

Sound. The first problem was getting over the towering Rockies. Based

on his reading of early explorer's reports, Hill felt that there had to

be the right pass out there.

Ever since the Lewis and Clark expedition, one had been rumored and Hill sent John F. Stevens to find it. On December 11, 1889 the obdurate Stevens reached his objective. Marias Pass, at an elevation of 5,215 feet is the lowest point on the continental divide from Canada south almost to Mexico. Less than two years later, on September 14, 1891, Great Northern's rails reached the summit. Two Medicine trestle under construction in 1891.

Local passenger service was offered on the Pacific extension as the Haskell Pass tunnel was being built. In 1891, Barney & Smith delivered an additional four 10 section, 2 stateroom, single smoking room sleepers named Kalispell, Kootanai, Snohomish, and Seattle. The maroon grooved-sheathed cars were built with enclosed vestibules and thier names reflected the new expanded service on the Pacific Extension. Great Northern began running trains No 3 & 4 through Kalispell on August 17, 1892. The consist included sleepers, day coaches, dining cars and free Colonist sleeping cars. Once passenger service was extended over the Pacific extension, service between Havre and Butte became trains 23 & 24.

According to Arthur Dubin

The nations most northerly railway, serving a sparsely populated territory and labeled "Hill's Folly" by disbelievers was an immediate success. Every component was first rate. The longest tangents, easiest curves, heaviest rail, and finest equipment - Jim Hill would tolerate nothing lessBoth trains still carried the same equipment daily: sleepers,

day coaches, dining cars and free Colonist sleeping cars. Train No. 23

met No 3 at Havre where the Butte and Great Falls sleepers were exchanged,

and the reverse occurred as eastbound No 4 met No 24. Coach passengers

walked across the platform. Construction continued west. Between the fall

of 1891 and the following spring, as the Haskell Pass tunnel was being

dug, GN track layers continued on the west slope of the Salish mountains

reaching the Kootanai River at Jennings in 1891. Track layers followed

the Kootanai through the Cabinate mountains to the Idaho panhandle, and

crossed into Washington at Newport. They turned south at Newport, following

the Little Spokane River down Scotia Hill towards Spokane Falls. On June

1, 1892, the railway arrived at Spokane, coming down a one percent grade,

from what was later called Hillyard, and used a portion of the Seattle,

Lakeshore and Eastern right-a-way along the north bank of the Spokane

River. By 1890, the OR&N had become the Pacific division of the UP,

but was carrying traffic to Portland for the GN, & NP as well as the

UP. GN had good relations with OR&N, using its ornate Spokane depot

located on the north bank of the Spokane River between Howard and Division

streets between 1892 and 1902. The location was directly across the Spokane

River from Havermale Island, the site of Great Northern's terminal in

| August 1892 | ||||

| Westbound | Eastbound | |||

| Train #3 | Great Northern | Train #4 | ||

| (Sun) | Dep 7:10 PM | St Paul | Ar 6:55 PM | (Fri) |

| Tue) | Arr 6:30 AM | Havre | Lv 6:45 PM | (Wed) |

| Train #23 | Montana Central | Train # 24 | ||

| (Tue) | Lv 6:30 AM | Havre | Ar: 6:45 PM | (Wed) |

| (Tue) | Ar 11:15 AM | Great FallsAr: 1:45 PM | (Wed) | |

| (Tue) | Ar 7:15 PM | Butte | Lv: 6:45 AM | (Wed) |

| Train #3 | Great Northern | Train #4 | ||

| (Tue) | Ar 7:00 PM | Kalispell | Lv: 7:30 AM | (Wed) |

| (Wed) | Ar 6:00 AM | Spokane | 7:30 PM | (Tue) |

| Train # 6/1 | OR&N Railway | Train # 5/2 | ||

| (Wed) | Lv 7:00 AM | Spokane | Ar: 7:15 PM | (Tue) |

| (Wed) | Ar 6:50 PM | Pendelton | Lv 5:42 AM | (Tue) |

| (Thu) | Ar 7:25 AM | Portland | Lv: 7:30 PM | (Mon) |

| Running Time | to Portland | 84 Hours |

The OR&N connection at Spokane offered a 24 hour trip to Portland. Westbound GN Number 3 arrived in Spokane at 6 AM to connect with OR&N's Number 6 which departed at 7 AM. Number 6 reached Pendleton, Oregon at 6:50 PM where it connected with westbound train No 1, the Pacific Express. Number 1 arrived in Portland Union Depot at 7:25 AM the following morning Eastbound, the Atlantic Express, train number 2, departed Portland at 7:30 PM, reaching Pendleton at 5:42 AM. There, connects were made with No 5 which arrived in Spokane at 7:15 PM. GN's number 4 left for St Paul 15 minutes later at 7:30 PM. The scheduled through time between St. Paul and Portland in 1892 was 84 hours. The N.P. by this time had terminated its OR&N connection, routing its trains from St. Paul via Tacoma to Portland, with a running time of 101 hours, or 17 hours longer than GN

Through GN cars to Portland did not begin operation until 1895, when an agreement was reached for the OR&N to carry GN sleepers and coaches through to Portland. GN schedules of the &N Portland service as the Oregon line.

Washington Line

| Nov 1892 | ||||

| Westbound | Eastbound | |||

| Train #3 | Great Northern Railway | Train #4 | ||

| (Sun) | Lv 7:40 PM | St Paul | Ar: 6:55 AM | (Mon) |

| (Wed) | Ar 6:50 AM | Spokane | Lv: 6:00 PM | (Fri) |

| (Wed) | Lv 1:00 PM | Spokane | Ar: 8:20 AM | (Fri) |

| (Thur) | Ar 5:30 AM | Wenatchee | Ar: 4:00 PM | (Thur) |

| (16:30 hrs) | (16:20 hrs) |

GN obtained trackage rights on the OR&N for one mile between the OR&N station and GN junction on the west end of town. From there, the line crossed over the Spokane River on a high bridge passing behind Fort Wright. Track laying began west of Spokane on July 18, 1892, building towards Puget Sound. By the end of 1892, only a seven mile gap remained in the Pacific Extension. West of Spokane, twice a week service was extended to Wenatchee on November 14, 1892.

The Spokane LS&E depot in Spokane, used GN 1892-1902 The Spokane LS&E depot in Spokane, used GN 1892-1902 |

Initially, the trip took 23-´ hours but was soon shorted. Number 3 left Spokane at 1 PM on Mondays and Thursdays arriving in Wenatchee 16-1/2 hours later at 5:30 AM. The equipment was turned and number 4 left Wenatchee eight hours later at 4:00 PM on Tuesdays and Fridays. The overnight train arrived in Spokane the next day at 8:20 AM. Passengers enjoyed a boat crossing of the Columbia River since the bridge was under construction. The St Paul - Wenatchee trip was 1653 miles.

Start of Service

On January 6, 1893, in an impromptu ceremony, one and three-fourths miles east of Scenic, Washington, a plain iron spike was driven home to complete Great Northern's Pacific Extension. Traffic had not yet been developed, equipment not yet provided, nor the telegraphic lines constructed. Great Northern faced the daunting task of building both a plant and traffic with neither subsidies nor land grants. The ceremony at Scenic,Washington was only the first step in the completion of the GN.

|

Another month would pass before a regularly

scheduled train worked over the line. Six months elapsed before the first

transcontinental, regularly scheduled passenger trains ran between Seattle

and St Paul. As passenger service was being inaugurated, ceremonies were

held in July at St Paul and Seattle to mark the completion of the line.

Original Mainline

The June 1893 mainline differed from its route of later years. The 1827 mile route to Puget Sound ran through substantial wilderness followed ten rivers and crossed three major passes, Marias, Haskell, and Stevens. From St Paul, the original mainline went northwest through Elk River, St Cloud, Fargo, and Moorehead to Grand Forks, North Dakota where it turned west towards Devils Lake. It followed the high line through Minot, Williston and Havre, Montana to crest the Rockies at Marias Pass. The mainline descended into the Flathead Valley to Kalispell. It proceeded west through the Salish mountains over the 1-1/2% grades of Haskell Pass reaching the Kootanai River at Jennings. The Kootanai was followed through the Idaho panhandle to Newport, Washington where the line swung south to Spokane. The GN operated over a mile of trackage rights over the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern through downtown Spokane. From Spokane it went west to the Columbia River and Wenatchee.

The Cascade Switchbacks |

The weakest link in GN's route was the line across the Cascades. There, Great Northern had to accept a temporary line with torturous switchbacks until traffic grew to the point that justified the planned tunnel.

After topping the Cascades, the route followed the Skykomish River to NP's Delta Junction and Everett. It then followed the shores of Puget Sound, with its mudslides, to Seattle and its Railroad Avenue Terminal.

The Eastern end of the line between St Paul and Havre had been in service for several years. 4-4-0s had proven satisfactory pulling open platform cars.

When service between Havre and Spokane was established in 1892, heavier power was acquired.

That year, Mogals joined the remunda to handle trains over Haskell and Marias Passes. Soon the mogals were augmented by 2-8-0 and 4-8-0s as helpers. For the new Puget Sound service, operations over the Cascade line had to be developed and would prove to be the most difficult. In the Cascades, the Mogals could handle two or three cars over the 4% grades and switchbacks. Normally, three locomotives were required to move a seven car passenger train over the Cascade summit, taking 1-1/2 - 2 hours to cross the switchbacks. Maritime operations played a significant role in the development of the GN. The Northern Steamship Company, formed in June, 1888, was the first maritime venture. The steamship Northwest went in service in 1894, followed by the Northland in 1895 between Buffalo and Duluth. Carrying 758 passengers, 544 first class and 214 second class, they were fast and luxurious. Biweekly service was offered between Buffalo and Duluth where passengers could make connections to GN.

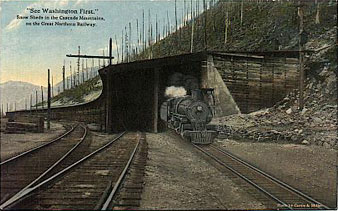

An 'L' class mallet exiting a snowshed at Wellington in the Cascades |

Six months elapsed from the completion of Great Northern's line between Seattle and St Paul on January 7, 1893, and the commencement of transcontinental passenger service. The first train that left St. Paul on June 15, 1893 carried no name and was simply known as numbers 3&4. In 1895, Great Northern began calling the train the Limited. The more familiar Great Northern Flyer name was applied in 1899, with the train being renumbered from 3&4 to 1&2 in 1903. The Great Northern Limited moniker was used briefly in 1905, until the renowned Oriental Limited designation was adopted in December. In starting its transcontinental business, Great Northern faced stiff competition from the Canadian Pacific, Union Pacific and especially the Northern Pacific. To build traffic, Great Northern began an ambitious immigration program to populate its route. The immigration program pursued by Great Northern was a success. By 1903, traffic and business warranted a second transcontinental train. The Puget Sound Express westbound and Eastern Express was added, assuming numbers 3 &4. GN changed the train's name three times in twelve years. In 1906, 3&4 became The Fast Mail; in 1910 they became The Oregonian; and finally in 1915 the name The Glacier Park Limited appeared, promoting its on line tourist attraction.

Great Northern's 1905 advertising proclaimed

"To have a new way across America is itself a great achievement and it becomes doubly so when it is coupled with the fact that the way is the shortest, easiest and most interesting route across the continent. This is the case of the youngest and already one of the greatest transcontinental lines, The Great Northern Railway.

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exhibition was held in Seattle in 1909. For the expected traffic, the Oriental Limited was refurbished and a third transcontinental train entered service, between Seattle and Kansas City via Shelby, Great Falls and Billings. The train to the Missouri Valley was initially called the Northwest Express westbound and The Southeast Express eastbound. The westbound's name was changed to The Great Northern Express within a few months.

Recap of Transcontinental

Trains

1886 - 1929

St paul Minnesota & Manitoba

| Manitoba - Pacific | 1886 -1893 |

| Montana Express | 1887 -1890 |

| Montana - Pacific | 1889 -1892 |

Great

Northern

Primary 3&4

1893-1903 then 1 & 2 1905 onward

| No Name Train | 1893-1895 |

| Limited | 1895-1899 |

| Great Northern Flyer | 1899-1905 |

| Great Northern Limited | 1905 |

| Oriental Limited | 1905-1929 |

| Empire Builder | 1929 - |

Secondary 3 & 4

| Puget Sound/Eastern Express | 1903 -1906 |

| Fast Mail | 1906 -1910 |

| Oregonian | 1910 -1914 |

| Glacier Park Limited | 1914 -1929 |

Missouri Valley 43 & 44

| Northwest Express | 1909 |

| Great Northern Express/Southeast Express | 1909-1918 |

Third Mainline

Great Northern's Transcontinental Trains are covered in other articles

and are not repeated here as they were in the reference sheet. A third transcontinental line was completed in 1916 between

Spokane and Vancouver, B. C., revenue passenger trains never operated over it. Operation was very slow since the line was twisty and

turny with heavy grades. GN realized that it could more efficiently route

through traffic to or from Vancouver south to Everett and east over Stevens

Pass. Thus, GN quickly treated its Spokane-Vancouver route as a branch

line.

An early GN station in Minnesota

An early GN station in Minnesota